A Teacher’s Story

Seosamh Ó Drisceoil

Born 1924

My earliest memory is of being placed in a horse collar by the hob watching workmen taking dinner at the kitchen table. As far as I can establish now I was hardly one year old at the time. The men were building a hay barn in the haggard behind the house.

I was born in the early twenties in Dunbeacon, Durrus, West Cork, the youngest in a family of four boys and three girls. My parents had a small farm - the grass of nine cows - but they also kept a sow roaming in the field. At times we were fattening half a dozen bonamhs which were fed skimmed milk, small potatoes and the leftovers from the kitchen.

We practiced mixed farming so as well as the animals we had wheat, barley, plenty of turnips, potatoes and parsnips. My mother kept a kitchen garden at the gable end of the house where she cultivated vegetables and a variety of fruits. She was an industrious woman who used the produce of the farm to keep food on the table.

I remember that I had an old fashioned wooden cradle as a bed as was the custom at the time. As soon as I was ready to share a bed with my two brothers the cradle was given to a relation who was expecting her first baby. At that time boys were not dressed in trousers until they were ‘trained’ – they wore skirts while they were toddlers.

Farming life became more difficult as we moved into the hungry thirties. It was much worse however for the labourers who had few worldly goods. Homemade bread, potatoes, vegetables and tea comprised the normal diet of rural households at that time.

Farmers who kept pigs would slaughter one in the Spring and another in the Autumn, providing bacon for the table throughout the year. I will never forget the day that Johnny Pats, who was our local butcher, arrived at our house around ten in the morning. Killing a pig was a big occasion. We would all rise early that morning. I would have to help my brother Paddy draw water from the well. My mother and a neighbour would boil the water in large pots over the fire in the open hearth. My sister Peg was sent to collect delph from our aunt’s house. The older boys would clean the pigsty and the farm yard. My father would ensure that all the equipment was in good working order. There was a large wooden barrel and a pulley to haul the pig up under the rafters. There were also spancels, a whet stone and a butcher’s knife placed on the table. The special ritual of killing a pig was always strictly adhered to.

Farmers who kept pigs would slaughter one in the Spring and another in the Autumn, providing bacon for the table throughout the year. I will never forget the day that Johnny Pats, who was our local butcher, arrived at our house around ten in the morning. Killing a pig was a big occasion. We would all rise early that morning. I would have to help my brother Paddy draw water from the well. My mother and a neighbour would boil the water in large pots over the fire in the open hearth. My sister Peg was sent to collect delph from our aunt’s house. The older boys would clean the pigsty and the farm yard. My father would ensure that all the equipment was in good working order. There was a large wooden barrel and a pulley to haul the pig up under the rafters. There were also spancels, a whet stone and a butcher’s knife placed on the table. The special ritual of killing a pig was always strictly adhered to.

Pats sharpened the knife after rubbing oil onto the stone. He made a clean cut of a rib of hair from his beard on the first attempt. He placed his finger in the hot water and was satisfied. He checked the pulley and when he was satisfied that everything was in order he rolled up his sleeves and everyone knew that the drama was about to begin. I admit that I did not enjoy this work - the pigs were regarded as pets as we had cared for them from the day they were born.

When I was young the sow was brought into the kitchen as soon as she seemed likely to farrow. Two of us would mind her throughout the night and as the weanlings came we ensured that the sow did not lie on them. There would be about a dozen in the normal litter but if there were more they were bottle fed as there were not sufficient paps for them all. These weanlings were called Íochtars and were special pets. There were many Irish words in use by the farmers in the area while I was growing up. I have collected approximately three hundred Irish words, which were in common use at that time.

When the pig was killed it was hauled up to the rafters with the pulley, so that it could be lowered into the barrel of boiling water. Then it was shaved and the intestines were removed. The carcass was hung at the end of the kitchen for a day or two until it was ready for curing. The grisceens and the cruibiní were distributed amongst the neighbours and the salted bacon was placed in a barrel to cure. Today if you had the same meat every day of the week you would get fed up with it, but I can tell you we never got fed up with our home cured bacon.

There was no creamery in the locality when I was growing up. Instead we had a separator in the kitchen which was used to separate the milk morning and evening. The cream would be churned once a week and there was great demand for the buttermilk for baking. We would drink it fresh and my grandmother would say that it gave us rosy cheeks. There were many pisroges in the area. Anyone who entered the room had to take his turn at the churning. Some misfortune would surely befall the company if this custom was ignored.

There was a poor widow known as Bríd Rua living in a small thatched bothán on the way to my uncle’s house. When we were visiting him my mother would give us a can of buttermilk to leave in to Bríd Rua. We did not understand for a long time the reason for the large lump of butter that would be left floating on top of the can.

My mother never wasted a penny. She was always knitting socks and jumpers. She made every item of clothing we wore and all that needed to be bought was footwear. Unfortunately being the youngest, I got all the ‘hand me downs’.

Parcels regularly came from America. Many girls emigrated in those days to work in big houses and wore the clothes that were being thrown out. We were fortunate that a friend of my mother was working there at the time. My mother made a very fine First Communion suit for me from a parcel that came in that way.

Shortly after my parents’ marriage a female relation of my mother died leaving a family of six with an alcoholic father. The children were divided amongst the relations and the youngest girl, Jane came to live with us. She was the same age as my eldest brother Jimmy. She attended the local school and grew up to become a fine young woman. She was readily accepted as a member of the family and was a great help to my mother. One by one the older girls of that family emigrated to America. When Jane was nineteen her sister sent her the money to pay for her own fare to the States. The day my father brought her to the train station in Bantry they were forced to ford the river as the bridge had been destroyed the previous night by the local Republican forces – the Civil War was raging at that time. Jane always remained a faithful friend of the family.

Few children attended school in those days until they were five years of age. Although we had a walk of a mile and a half many more had much longer journeys. I have no recollection of my first day at school - no great deal was made of it at the time. I walked together with the other children who looked after me. Around that time a fundamental change took place in the educational standards of the school. Until then a married couple had been teaching there. They both retired at the same time. Neither had much Irish and they did not benefit much from the language courses they took in Béal Átha an Ghaortaigh. Everyone was delighted when a new principal was appointed who was both fluent in the language and who had a great interest in promoting it. The same was true of the new mistress and there was great understanding and cooperation between them both. The Mistress used the storytelling method to teach Irish and in no time at all she had laid down a good basic foundation. She would write stories on sheets which were hung on the black board, one every week. We learned the stories by heart and were then questioned to ensure that we understood them completely. She would cleverly weave witty expressions, proverbs and sayings into the stories. We then had to compose other suitable situations to employ those expressions. I have no doubt that this was an efficient language teaching method and we all achieved fluency by the time we reached third class and the Master’s room. I still know some of those stories by heart - for example the Fox and the Crow. It should be understood that outside the school no one spoke Irish in the locality at that time.

When I was in the middle classes a travelling Irish language teacher came to the parish and organised night classes for adults in the school. The Master recommended to the older children that they attend, and both my brother and I did so. There was no electric light in the school and we used Tilly lamps, creating ghostly shadows in the room. This excellent teacher was a native speaker from Cúil Aodha and we all benefited from his classes. He had a richness of language which he shared generously with us all. When he was dealing with the weather, for example, he gave us expressions such as “Ceo ar Mhuisire, Clárach lom, an comhartha soininne is fearr ar domhan.” This referred to two hills, Muisire the taller and Clárach the lower. When Muisire was shrouded in fog and Clárach was clear, this was a sign of good weather to come. Amongst the prayers he taught us in Irish was “Go raibh ainm mhilis Íosa go taithneamhach scríofa i lár mo chroíse. A Mhuire Mháthair Íosa, go raibh Íosa agamsa agus mise ag Íosa.” Both this man and my regular teacher had a great influence on me - they first showed me the great wealth of our native language.

Another incident took place one night while we were attending this class. Our next door neighbours had a pony and a donkey grazing in a field beside the road. We let the donkey out, the two of us mounted it and off we went. We put ‘Neddy’ into a field by the school, closed the gate, and she was waiting for us when the class was over. We should have known that the pony would become very agitated when its companion was removed. Not surprisingly our neighbour was driven to distraction with worry that the animal would harm itself. And of course the story got out that we were the ‘scuts’ responsible. The neighbour complained us to our father and we paid dearly for that escapade. Only for my sister Julia, the second eldest in the family, matters would have been much worse. She was like a mother to me, the íochtar or youngest of the family...

The first time I heard Irish being spoken outside the school was by the natives of Cape Clear island at the regatta in Schull. My father was accustomed to harness the trap and to bring the entire family to the event which was held every year on the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, the 15th of August. The seaside town would be packed, the country people dressed in their Sunday best, young girls in cotton dresses, street hawkers selling refreshments, three card tricksters, old women dressed in the local traditional cloaks and ice cream sellers. There was also a group of young islanders, about my age, conversing animatedly at the end of the pier. I drew closer to them and although they were speaking very fast I could follow what they were saying. I understood for the first time that Irish was still in use as a language of everyday conversation in places throughout the country. This was a turning point for me - I decided to emulate them. By the time I was in fourth class we were taking all our subjects through Irish and it was the everyday language of the school. The teacher used the method known as A,B,C. In the first part, A, accuracy and fluency was emphasized. The second part, B, focused on normal everyday events in order to develop our vocabulary. And finally, C, every Friday the lesson was revised through conversation, drama or a storytelling. Not only that, but we did our religious education through Irish even though we had to take our Confirmation exam through English. The Bishop of Cork at that time was not supportive of the national movement. Wasn’t it he who had excommunicated Tom Barry !.

Those two teachers performed wonders in a non ‘Gaeltacht’ area and did not neglect the other subjects either. Before long the results of their efforts were evident to the wider community. Normally, one or two students were awarded County Council scholarships to secondary school every year. Of the three youngest in our family who came under their influence, two achieved civil service positions, and I was awarded a scholarship to attend the Preparatory Secondary School for teachers, Coláiste Chaomhín in Dublin.

I will never forget the day the letter came. My father brought it with him as he returned from the Creamery that morning. It was during the Summer holidays and I had been sent to the field to get potatoes for the dinner. I was digging when my father called me from the yard. There was some conversation in the background and before long I was called again. I was slow to respond as I had not completed the task in hand. Yet again I was called. Finally and not entirely happily, I collected what I had dug and made my way to the house. The entire letter was in Irish of course but they realised that it was important as it bore the harp on the envelope. I read it twice before speaking as it was so difficult for me to comprehend. I would be going to Dublin to become a teacher. I would be of equal standing to the post master, the priest or the doctor. No one even considered that I might not have the makings of a teacher.

But I had another problem to resolve. A short time before this a Christian Brother had made a recruitment visit to the school on behalf of the order. I had put my name down when I heard of the missionary work being undertaken throughout the world. Not only that, but I had already received a letter of acceptance and was on the point of entering the order. I consulted the teacher on the matter and he told me that there was little difference between the two choices and that I would probably end up teaching in any event. I decided accept the scholarship to Coláiste Caoimhín. We made a trip to the town and my mother purchased everything on the list from the College. At that time it was customary to purchase clothing in larger sizes than was necessary at the time, something which left me looking somewhat dishevelled. I spent the difficult years of the war in various boarding schools. This was a great change in my life. I had never spent a night away from home. I had no experience of electricity, running water, bathrooms or any of the other modern conveniences that were available in the cities. My first trip to Coláiste Chaoimhín was my first time on a train. Fortunately, there was a local girl returning to the city after the funeral of her mother, and I was placed in her company. The poor girl was so distraught that she hardly spoke to me during the entire journey.

We finally reached Dublin. My brother Paddy who was in the civil service was waiting for me in what was then called Kings Bridge Station. He left me at the college and it was then the loneliness hit me, on my own among two hundred students, with not a familiar face in sight. To make matters worse I could not understand one word being spoken by the College President, Brother Ward, as he was discoursing fluently in the Ulster dialect. There were students from all over the country and fortunately I had no difficulty in understanding Munster Irish. As time went on we all got to know one another and before the year’s end none of us had any difficulty understanding each other. Not one word of English was spoken in the place. I never felt any pressure regarding the language as it was the natural language of the great majority of the students. Even today when I meet anyone of that crowd we revert naturally to Irish. I made lifelong friends that first year.

There was a great emphasis in Coláiste Caoimhín on music and the sports of football, hurling and handball. Amongst the crowd that first year there were players who achieved great fame on the playing fields. Dónal Caomhánach and Parthalán Ó Gairbhí played with distinction for Kerry in the forties, Prionsias Ó Broin played as a corner-forward for Meath and Brian Ó Ruairc excelled with Galway.

Another student was Paddy ‘Bán’ Ó Broin, the only ‘Dub’ in the college at the time. He was a great man for music, dancing, football and telling yarns. He earned his nickname when he ran onto the playing field the first day with his curly fair hair and his Kerry jersey and Dan Larry called “By God, do you see Paddy Bán coming on the field”. He was referring to Paddy Bán Ó Brosnacháin from Dingle, a fisherman who was a full back on the Kerry team at that time. That nickname stuck with him for the rest of his life, may he have a place with the saints of Ireland.

We had permission to leave the college every Saturday and Sunday during the year. The worst thing was a rule that obliged us to always wear the college cap while outside the gates, a rule that was more often than not ignored. We spent much time in Woolworths on Saturdays and we would attend Croke Park on Sundays when games were being played. During that time the great games between Cork and Kilkenny were played. We had a happy life in Coláiste Caoimhín and the seniors were kind towards us ‘hedgers’ that first year. Although there was one brother who was quite brutal the teaching staff were generally very understanding. We were informed that the college was to close at the end of that first year and that the junior students would have to go to Coláiste Éinne in Galway the following year. The defence forces occupied the college and made it their head quarters for the duration of the war. We were sad to leave the college and our friends that year. I never met many of those seniors since that time.

I spent the Summer holidays working on the farm at home. There was very little machinery used for cultivating at that time. We cut all the grass by scythe and would spend all June saving the hay. I was an accomplished scythes man by the time I did my Leaving Certificate. It was essential to be able to maintain the scythe well sharpened, to adapt it properly to oneself, to fix the blade so that it would not become entangled in clumps and to keep it parallel to the ground. There was great demand for good scythes men and I was often hired out to neighbours.

While we had a barn at the time many of our neighbours made do with hay reeks instead. After consulting with the local ‘experts’ the day was set. Weather forecasts were not broadcast as they are now. The farmers depended on the signs of the weather that were around him. If the wind followed the course of the Sun from the east in the morning to the west in the evening and calmed at nightfall that was considered a good sign. As a result of these signals the neighbours would be called to make the reek on a particular day. The weather rarely failed them. The men would gather after returning from the creamery. They would be divided into groups and each group given a different task. One group would bring the hay in from the meadow, another would lay out the cocks and yet another would prepare the base of the reek in the haggard. It was necessary to lay a good base of branches and straw first to keep the reek free of dampness. Three were appointed to go up on the reek. Two strong men were appointed to throw the hay up on the reek and a special person, the most important of all was the gaffer in charge of building the reek. There was an old man known as Dinny Mike who was known as a good reek maker in our town land and it was reputed that no reek of his ever let in a single drop of rain. The young lads were tasked with drawing the hay, the worst jab of all as the hay seed would become entangled in your hair and eyes.

As the reek was getting higher one man had to stand on a ladder to throw the hay up to the men on top. There would be a keg of porter in the corner which was badly needed because much sweat was lost by that hard work on warm sunny days. One man might have a great thirst and spend the day sampling the porter. When the work was finished and the tea drunk most of the men hurried home to milk the cows. But Dinny would remain with one or two others to place a covering of rushes on the reek. The súgán was turned and everything left in good order before the last ‘drink for the road’ was consumed. That man had three daughters and one son.

Sometimes the day ended with a ‘scoraíocht’ in Dinny’s house. The young people of the district would gather in their ones and twos until the house was full. An accordion was brought down from the loft and sparks flew from the flagstones as the sets were danced. No matter how much sweat was poured during the day more still was used up during the evening as the craic lasted until dawn. There was no dance hall or cinema close by in those days. We gathered in the houses of the district during the winter and made our own entertainment. Some houses had old people who were good at storytelling. Others were known for card playing and a house with three or four girls would host ceilís. Around that time the “hops” were started in the parish halls, where the Priest could keep an eye on things. These used to end at eleven and no young man who had drink taken was allowed admission. However the ear of the “hops” did not last very long.

Two events occurred during that time which fundamentally changed the social life in the countryside. Before this we would travel everywhere by bicycle. With the coming of cars our range increased considerably. At the same time the large bands came into fashion and large halls were constructed in the towns. The young people moved out of the country districts and the small parish halls to attend these new venues. The simple life of the countryside was over.

The Second World War started in September 1939 and we were delayed going back to college. A ship was sunk off the Galway coast by a German submarine and the survivors were temporarily housed in the college and we were give an extra fortnight’s holidays.

I now had to spend a night in Cork on my way to Galway as it was not possible to make the trip in one day. The first thing the College President said on our arrival was: “Those that have fees to pay come to the office immediately”. In spite of the cold welcome we enjoyed the year we spent in Coláiste Éinne in the City of Tribes. We came to know the Taibhdhearc Theatre during the year and some students even performed there. There was a great difference between Coláiste Chaoimhín and Coláiste Éinne as Coláiste Chaoimhin was located in the Capital City and the students had access to social, cultural and recreational outlets of all kinds. There was the National Library, the various museums, the National Gallery, the theatres, the Zoo, the Botanical Gardens and many other institutions to attend. But it was in the atmosphere of the college that the greatest difference was experienced. The Christian Brothers had long experience of managing colleges and had a much greater influence on the day to day lives of the students. They got to know all the students and no one was reluctant to seek their help or advice. They helped anyone who was unhappy or having difficulties. Things were entirely different in Coláiste Éinde. The college was situated in a windblown site on the edge of the City. The newly constructed building had little character and there had been little development of the surroundings. The college was under the patronage of the local dioceses and they had little personal contact with the students. It was the lay teaching staff that gave most attention to the students. Professor Aodh Mac Dubháin in particular comes to mind. He had wonderful native Irish and a great ability in acting which he shared generously with the students. It was he who introduced us to the Taibhdhearc. The Munster Students who were amongst the student body were never entirely at ease in the place. They understood that they would not be there at all had Coláiste Íosagáin in Munster been completed on time.

Ballyvourney, Co Cork where Coláiste Íosagáin was located was an entirely different place. The college was situated in the countryside in the Sullane Valley between Ballyvourney and Ballymeekeera. There was a fine farm attached to the place and many trees and lush growth in the area. There was some Irish still spoken in the district and of course Coolea was nearby. A local storyteller would come into us from time to time and he had his own version of the Fianna stories. He also told many stories about the local patron saint, St Gobnait as well. We got to know the local people and they would invite us into their homes.

Many visitors came on pilgrimage to St Gobnait’s well and some of them even spent the night in the old ruins. There were many stories of people who had been cured by drinking the water from this holy well. St Gobnait's feast day was observed as a holy day of obligation in the parish and the students enjoyed a day off also. O’Sullivan Bere spent a night here on his famous retreat to Breifne after the Battle of Kinsale.

We had to grapple with yet another dialect during our time there. This was for the best as we became accomplished in all dialects by the time we finished college. We spent two more hungry years in Coláiste Íosagáin which was run by the De La Salle Brothers. That was the first year the college opened and it was in a great condition. There was a great deal of land around it, wide playing fields, a farm which produced all the vegetables used in the college, a beautiful river which ran through the grounds into the Sullane and mature trees all around. Across the road there were the ruins of St Gobnait’s Convent. There was a great emphasis on football and we spent every available moment on the playing fields. The greatest drawback was that we were constantly hungry. The situation worsened during our second year there and our patience broke in the end. The students in the Leaving Certificate class decided to strike the week before the exam. We sent a delegation to the President to no avail. We refused to go to classes and instead marched down to the village and each of us purchased a loaf of bread. We returned with the bread and consumed it on the green in front of the college. The President called us one by one to his office and told us that we would not be accepted into the Teacher Training College - however if we told him who the instigators of the strike were, there was a chance we would be accepted. Not a single person informed. He then ordered us into the Study Hall and ordered us to write letters home looking for train fares as he was planning to expel us all from the college. We all wrote looking for bags of flour as there was insufficient food in the college. We had to deliver the letters to the brother and I don’t imagine that they were ever posted. He did not permit us into the library or the study hall until the exams started. During the Summer holidays he wrote to all the students again trying to get information on who were the leaders of the strike. Obviously no one told as we were all accepted into the teacher training college.

We enjoyed much more freedom in St Patrick’s College of Teacher Education and a greater variety in the curriculum. While I have always enjoyed listening to traditional music I couldn’t put two notes together. When I said this to the Professor of Music Mr Redmond, he told me that there was no such person as someone who could not sing a song. Sadly, in spite of my every effort to cooperate with the poor man, I was a complete failure in this regard. The same man had a great sense of humour and I can recall him defining the musical expression syncopation as “a drunk staggering from Mooney’s to Madigan’s!”.

The Professor of Education, Jacko Piggott regularly advised us: “Write your love letters in pencil but write my notes in ink”. We afterwards discovered that this was sound advice indeed. Those two years slipped by quickly as we were very interested in the work we were doing and understood its importance. There was a great variety in the work also because in addition to attending classes we had to review sample classes, go out to schools on teaching practise and prepare class notes. We spent three consecutive weeks on teaching practice in city schools. No two schools were the same. All of the professors would visit us during that time but we were unconcerned about them all except the Professor of Education. He always had the last word. We had to prepare notes for each class and always kept the best ones for his visit. It was necessary to prepare an introduction, presentation of new material and the implementation strategy for each lesson. The introduction recapped the information that the child already had, the meat of the class consisted of the new material being delivered and at the end you presented the students with problems to help them memorise the lesson. There was no talk that time of child centred education - we were teaching classes the whole time. Although that old teaching system had its faults the teachers that came from those Colleges generally had a positive impact on their students.

It was mostly football that was played in the college at that time but some of us practised with the Sliotair also. I can recall on football match which the college team Éirinn’s Hope played against the Vetinary College. Nicky Redmond, that giant of a man who gave so much of his life for Wexford was on the opposing team, as was Weeshie Murphy who played as full back for Cork. They were close friends throughout their lives. They would go around the City on one bicycle together, one cycling and one on the cross bar. The bicycles made at that time were sturdy !.

The course ended with a formal dance in the Crystal. Some of the lads had problems finding partners and sisters were in great demand. I know of one couple who first met that night and who spent a long and happy life together thereafter. Although we all enjoyed the evening it was a sad occasion also for I never met many of that crowd again.

My eldest sister died from the Yellow Jaundice that Summer. It was many a pound that she sent me while I was in college - she knew that money was tight. He death was a devastating blow to my mother. A light was extinguished that day that never shone again.

It was exceedingly difficult to obtain a position in those years. God only knows how many applications I sent away that summer of 1944 but I did not receive an answer to a single one. There was no talk of CV’s either. What was required was a letter of recommendation from the parish priest or better still a blood relation - no matter how distant - of the school manager. Well into the Autumn when I had lost hope the College President sent me news that a position for one year awaited me in the Carriglea Industrial School in Dún Laoghaire. He strongly advised me to accept the offer as I would be available if a permanent position arose in the city. It proved to be excellent advice.

I was reluctant to undertake this position as I considered that there would be disciplinary problems in an industrial school. In addition, I did not wish to go back working with the Brothers after the considerable time already spent with them. But I had no choice and so off I went to Dún Laoghaire. I was mistaken regarding the type of child in these schools. The were nearly all nice children but some misfortune had befallen their families that left them placed in the school by the courts. I had no problem with them and all the teachers endeavoured to foster their self-esteem.

The brothers welcomed me and placed third class under my care - they were all boys of course. The Principal presented me with a leather strap the first day and advised me not to spare it. Although discipline was strict I saw no brutality in that school. The war was still in progress and although foodstuffs such as tea and shop bread were in short supply the young ones in that school were well treated. There was a good standard of education and students were seldom absent. Some of them had to attend the courts from time to time. The thing that most bothered the teachers was that we had to return to the school by rota in the evenings to supervise the study.

I did my first diploma exam in that school and fared quite well. We were given prior notice and I had both notes and corrections under control. The inspectors at that time placed great emphasis on the correcting of the copy books. The teacher was obliged to present him with the copy books and he would study them in detail to ensure that each mistake was corrected. Otherwise they would be marked with the red pen. One day I was taken aback when the principal escorted two strangers to my room. One of them was a trainee inspector accompanied by the head inspector. The young man who made the inspection knew my people well although I had never met him personally. He put me at my ease from the beginning and I continued teaching the lesson that I had already prepared. He put a few questions to the children after each lesson, always choosing the brightest ones – he had plenty of experience of teaching in the city !.

I only spent six months in that school when a permanent position was offered to me in City Quay National School on the south side of the Liffey. This was a poor area with much unemployment. There was good enough money to be earned by the dockers who worked the ships but there were strict rules regarding the their employment. It was a closed occupation and only the sons of dockers were accepted into the union.

Something interesting would happen when cargos of coal were being unloaded on the quay beside the school. The lorries would be overloaded and as they came around the corner you would hear the squealing of the brakes and the sound of falling coal. Then all the women would emerge from the doorways and would collect the coal in their aprons. They certainly didn’t go cold in the winter!

Although few parents of students attending the school had much by the way of worldly goods they had something much more important. There was a great spirit of charity and they all shared generously with one another. As I came to know them better my esteem for them increased and theirs for me. I was not long in that school when the principal entered my classroom one day and must have seen the strap which I had brought from my previous school. After a short conversation with me he gave me advice which greatly influenced my entire teaching career. He said: “ Many of the children in this district have a difficult enough life already. Don’t you make it more difficult for them”.

I was very interested in games and especially the GAA. I learned early in my teaching career that the teacher who promotes games has a greater influence on the students under his care. After settling into the new school one of the first responsibilities I undertook was to bring the students out after school hours to practise Gaelic football in nearby Ringsend Park. Until then the children played only Soccer, a game which was very suitable for the small streets surrounding the school. I got great satisfaction from the effort and they soon had the basic skills. I understood that I needed to arrange a match for them soon or that they would lose interest. I had a friend teaching in a small school close to Dublin Airport and we arranged a match. We went out on the bus one Saturday and had a wonderful day. This was the first time for the majority of these children being in the countryside. There were green fields surrounding the airport at that time and we played the match in one of them. The children greatly enjoyed the game. It was still a draw as the game was coming to an end. Unfortunately a large airplane came in over the field to land in the airport. As the other team were used to this they continued playing. On the other hand my boys were so terrorised that they threw themselves at the ground watching this monster coming towards them. As they did the other full forward put the ball at the back of our net without any problem at all. Although we lost that first match the days’ events were a talking point for a long time afterwards.

Around that time I came to know a teacher who was active in the Primary Schools League and he advised me to join. I was greatly welcomed and given all kinds of assistance. I met the most warm hearted and broad minded teachers who spent a great deal of their time and energy serving the children of the city. We enrolled in the small schools section in the football at first and later in the hurling section. We did not prosper in the hurling, something which proves to my satisfaction that a local tradition is needed in an area to succeed in this sport. We went from strength to strength in the football which came to climaxing in the late forties which we reached the final. It is difficult to imagine the great boost in spirit that this trip to Croke Park gave these poor children. They finally understood that they were a match for all other children in the city. There was little attention paid to studies in the week preceding the final. The teachers took the opportunity to fashion flags, hats, ribbons, badges and bunting with the school colours. The children in the higher classes composed and learned a school song. An inspector visited the school during the preparations and was not impressed with the racket. He told me that I was interfering with the work of the school and wasting the children’s time. The principal and the other teachers supported me and when he complained about me to the school manager he fared no better. Things were changing at this time and we paid less heed to old fashioned inspectors - their days were numbered.

There were supporters in Croke Park for that final who had never been there before. One would hear people calling “offside” and “corner” to the referee every time the forwards gained possession of the ball. While we did not win the final on that occasion we did win it the following year. Some of the players on that team went on to achieve glory playing for clubs of both codes throughout the city. One chap who was a full back that day, Michael Byrne, went on to become the physiotherapist for both the National soccer team and the Galway football team.

Teaching life was pretty eventful in those days. I had not put a foot inside the school when I was enrolled in the Irish National School Teachers Association. One of the teachers in the school, Seán Ó Dubhghusa was very active in the union and he made sure that every teacher was in the organisation. Teachers used to be intimidated by the inspectors visits because their salary scale depended on the grade he awarded them. It was very difficult to achieve the “very efficient” grade as there was a limit set to the number awarded. In practise, regardless of how devoted and efficient teachers were, one had to wait until someone “very efficient” retired to achieve that grade and the consequent salary increment.

A strange story happened to a man who was the vice principal of our school around that time. It happened that he was absent for a week with the flu and had submitted a doctors certificate to that effect. Towards the end of the week while he was recuperating a photograph appeared of him in the Irish Times newspaper playing golf. This did not pass unnoticed by the Department. The Inspector visited him immediately on his return to seek an explanation. He said that his doctor had advised him to take fresh air. The Inspector was unhappy with the explanation and without examining the class gave him a six month notice and reduced his grade to “inefficient”. To make matters worse the principal died suddenly shortly afterwards and although the Manager wished it the vice principal could not be promoted to principal. Every teacher in the school refused to accept the position which remained unfilled for six months until the period of notice had expired and the vice principal was duly appointed.

In the early forties a new young crowd joined the Dublin branches of the INTO and some other branches throughout the country. They were no longer happy to put up with the educational system as it was at the time. They failed to make any progress through negotiations with the Department. Large meetings were organised throughout the country and things went from bad to worse. A comprehensive strategy was then prepared. It was agreed that the teachers in Dublin would strike and that teachers throughout the rest of the country would contribute to make up 90% of their salary. This was the first time an arrangement of this kind was made by a union during a dispute. No one liked being on strike and it was worse still to be picketing on the streets in front of the public. The only group that agreed with us were the children who were enjoying unaccustomed holidays.

The two events which most stick in my mind regarding that strike which lasted six months was the racket caused by a group of teachers in the Dáil Gallery and “Operation Shakespeare” in which I was involved. In the first instance the strike committee had arranged with a member of the opposition to raise the matter of the strike in the Dáil. A large group of activists from the union who had received initiations went to the public gallery. No sooner was the question put that the racket started. When it continued the guards were called to clear the protestors from the gallery.

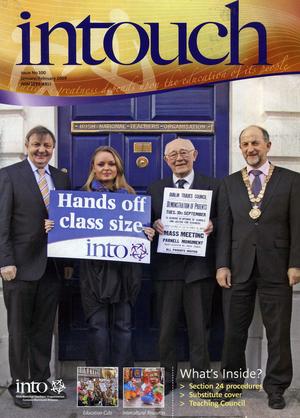

Some teachers were accustomed to meet in Shakespeare’s Pub in Donnybrook and it was there that the second demonstration was conceived. It was usual, then as now, for the Taoiseach and other senior ministers to attend the All Ireland Finals in Croke Park. The Shakespeare group decided to protest peacefully on the field before the Hogan stand where the VIP were seated during half time in the hurling final between Cork and Kilkenny in 1946. The protestors needed to be in the queues for the sideline places from early that morning. It was agreed that six protesters would sit in every corner and twelve in front of the Hogan Stand. As soon as the referee blew the whistle we all removed the banners concealed under our coats and rushed towards the Hogan Stand. The stewards had no time to intercept us and the demonstration passed off very well indeed. That demonstration received more publicity in the next day’s papers than the match itself.

While the State did not concede at that time and while we had to return to the classrooms after six months, matters started to improve from that time onwards. The punitive method of inspection was ended, pensions were improved, class numbers were reduced and the INTO was given a voice. Without a doubt that time was a turning point for the teachers of Ireland.

These protests also had a political impact. A new political party, Clann na Poblachta, was formed in which teachers were very active. That party did not last long but nevertheless left its mark on the country. While they were part of the first coalition government formed after the subsequent election the new Minister for Health Noel Brown instigated the program which saw tuberculosis eradicated from the country. Of course that government fell because of the controversy surrounding the ‘Mother and Child Scheme’ as it was then called.

There were major changes taking place in the lives of the city centre communities at that time. Housing was extremely bad, the people had no proper sewerage, living space or washing facilities. Because of the damage done by the air raids on the large European ports there was a policy to move people out from the cities to the suburbs. As a result of this the large families in the locality moved to Ballymun, Ringsend and Ballyfermot. The houses on the docks were left occupied by old people, something which left the families which had moved out without wider family support in hard times. Nowadays they are trying to attract people back into the cities because is doesn’t matter where an atomic bomb may fall, all will be destroyed. Because of this policy the attendance in the school fell sharply and we were left with five empty classrooms. I was interested in children who were not succeeding in the educational system as it then was. I decided to introduce more vocational education into the school. I obtained benches which were being discarded from a local vocational school and started woodwork classes for the children in the higher classes. We adapted the whole program to their own lives. At that time there was a committed inspector who agreed that this approach was far sighted. He advised me to apply for special funding from the Department and that such would be approved. It was in this way that the first ‘special class’ was started in the school.

The inspector also arranged with the Department that I would spend a year teaching in a special school to gain experience in the different educational methods in practise there. It was then that I saw at first hand the excellent work being carried out in these schools.

Around this time also a decision was made to amalgamate the two schools in the parish due to falling numbers. The other school, the girls’ school was a historical school, one of the first founded by Catherine Mc Auley and it was operated by the Sisters of Mercy. It was agreed to construct the new school on the site of the boys’ school. When the builders were preparing the site for the new school they discovered an unexploded shell directly under the floor of the class in which I used to teach. This was probably fired from the Helga during the Easter Rising of 1916. It took a year to build the new school and after the summer holidays a new chapter in the life of the parish began. The two schools had cooperated well over the years and the amalgamation was achieved smoothly. I was appointed the new principal. It would be hard to find more dedicated and devoted teachers than I had in that school. I spent over twenty years teaching in that parish and developed a great esteem for the local people. They were mostly very fine people indeed although they had little material wealth.

Not too long after the opening of the new school there was a great burgeoning of housing developments in the Dún Laoghaire area and plans were published to construct a number of new schools. I was interested in these developments as I was married by this time and had a home in the area. I was appointed principal of a new school to be built in Loughlinstown and we began our life in prefabricated classrooms which had already been used by another school. We had many difficulties at that time with people breaking into the school buildings. Eventually the matter was so bad that I had to bring the school rolls, the teaching aids and anything of importance home with me every evening. We bore it stoically while the new school was being built. Numbers were increasing at such a rate that although we began the year with two teachers we finished up with six. The actual site of the pre fabs was our major difficulty as they were over a mile from the housing developments we were catering for. The parents themselves arranged a private bus service to bring the children to school. This proved to be beneficial for the development of the new school. The same group organised fund raising events to improve the teaching aids and to provide other necessary facilities in the school.

At the end of the third year we finally moved into the new school. There was a major local celebration. The local politicians were present and the Minister present gave a longwinded speech promoting the various schemes being planned by the Department. The Chairman thanked everyone involved and invited us all for refreshments. The TD’s shook hands all round, no doubt, thinking of the next election !.

Without a doubt the site of this school was beautiful, built on a rise in the ground overlooking a stream and with plenty of open space all around. On the architects recommendation a low wall was built all around so that the children could sit on it and mind the place. They minded the place so well that every bush, flower and removable tree disappeared! The school was well laid out, running water and toilet facilities in each classroom, a large assembly hall, a library, a fine teachers room some distance from the main door and fine offices for the principal and secretary. Both the furniture and the place in general had a fresh smell. There were large windows and central heating. It was a great change from the load of turf my own father brought to the school at the beginning of each winter while I was attending primary school.

The area had many social problems. There was over 50% unemployment. The area developed a drugs problem and where there are drugs you will also find criminality, disorder and despair. But I must add that the great majority of families did their utmost to raise their children responsibly.

The school continued to grow until it was bursting at the seams. We had classes in the hall, the library and even in the porch itself. The second school should have been ready by now but it was delayed due to problems with the site. Finally we had no option but to divide the school, the junior classes in the morning and the senior classes in the afternoons. The parents were not too happy with this but we had no alternative. This system operated for a year and it was a great relief to us with the second school opened. I had only a few years left at this stage as my time was coming to an end. I determined to stay in charge of the junior school to allow a young and energetic teacher take charge of the senior school from the beginning. One of my staff was chosen and he proved to be a wise choice indeed. The two schools continue to serve the parish effectively to this day and have a good attendance.

I am retired now for more than ten years and its often I wander down memory lane. There have been many significant changes in the schools and the curriculum in the last eighty years, some of them as a consequence of the 1946 strike and the efforts of the INTO. The life of the teacher has improved enormously. Class sizes have fallen, the schools are more comfortable, salaries have improved, the inspectors visit is welcome and teachers enjoy a greater standing in the community. The situation is even better for the female teachers who have achieved parity with their male colleagues. They no longer have to retire on marriage or pay for substitutes during maternity breaks. When I started teaching the same curriculum had been in place since the foundation of the state. A new curriculum was later developed with more emphasis on the individual child. New subjects were introduced, environmental studies, art and crafts, health and fitness and citizenship. A new program was introduced for the teaching of Irish, Buntús Cainte. I doubt whether this was an improvement. I understand that yet another new curriculum has recently been developed to be hoisted on the teachers. Corporal punishment has been abolished. The health service for children has improved. Lunches were provided for children and grants to purchase school books. A library has been established in every school and boards of management were established which accorded parents their rightful place in the education system. When I started out we had slates and chalk as writing materials. When I retired computers were being used even by the children in the junior classes. Although we are used to bemoaning the old days I have no doubt that the young men and women of today are being well prepared for the lives that they have before them.

Excerpt from ‘Our Dublin Letter’, Southern Star 11.3.1950

The second function I attended was held in the town of Dun Laoghaire and this also was a lecture which was delivered by one who must have known the parishes of Caheragh and Skibbereen very well, but who has forbidden me to give publicity to his name for some unstated reason. The lecture also dealt with phases of the Irish revival with a background made up of the position of the language in the schools and homes of the Cairbre district, about the period when Tomás O Coinceannain, Gaelic League organiser visited that part of the country. References were made to a meeting held in Schull where Fr. O’Connor PP., presided and to a meeting in Skibbereen where Fr. Rom Kearney, who was then Adm. in the parish, presided. In the particular school where the lecturer learned his ABC Irish was never heard or mentioned,

‘Cois Life’

no one could there could read or write it in those days. In fact there was only one man in the parish who was reputed to know the written or printed language and he was a plain farmer wherever he succeeded in acquiring his knowledge of it. The farmer’s name was Mc Carthy and right away I knew who the man was. I knew that he was Paddy Mc Carthy of Castle, in Caheragh Parish. The position in the schools was pretty bad for the meanings of the names of the schools were never taught nor of the names of the neighbouring rivers, nor of the town land names, nor of the names of the fields where at play hour they raced at their games of ‘Sally’.

And the lecturer inquired if any of the audience ever took part in such a game. I think he knew that I knew all about it, but, to use a classic expression, I sang dumb. A young man, who I found to be a teacher in the town, said that he knew something about the game. I discovered afterwards this man was a Dunbeacon born O’Driscoll, who spoke Irish well, a fact that surprised me until he told me that his teacher was Tadhg O Foghlu of Béal a’Da Chab, and that in Tadhg’s time in that school all the pupils there spoke Irish fluently. I thought that I knew a lot about West Cork but here was a bit of good news from there I had never heard. I am glad to say that his pupil in Dun Laoghaire is a credit to the Balleydehob born múinteoir. He also stated that Tadhg O Foghlu had a way of teaching Irish that like magic gave an Irish outlook to his pupils. They found it the most attractive subject in the curriculum. Tadhg’s magic influence is no longer felt in Dunbeacon as he teaches elsewhere now, but I cannot at the moment recall the name of the lucky school where he teaches.

At the Dún Laoghaire meeting I also met an Irish speaking young lady whose father I knew very well many years ago. He was born in the district of Ros O gCairbre and was a well known figure in the Creamery world as we knew it then. He visited the U.S.A. on at least two occasions in connection with this work in that department. He was of the O Heigeartaig clan but I cannot remember his Christian name. He retired from his work some years ago and lives in the progressive borough of Dun Laoghaire at present. There too I met Irish speaking relatives of Ballineen people of the O’Driscoll family. Their mother is Maire Ní Raghallaigh who, though London born of Irish parents, acquired a fair knowledge of the Irish language, and was a favourite singer at Gaelic entertainments in London. Her family and relatives entertained many prisoners on their return from English jails after the 1916 Rising. Maire NíRaghallaigh is now Mrs O’Sullivan and lives in Dun Laoghaire. Her son and daughter are active workers in the Gaelic Circle there and are fluent Irish speakers. I am glad to see that they are very proud of their London born Irish hearted mother.

Their presence at that meeting and their knowledge of Irish set me thinking of the families of Irish born mothers who learned Irish songs in schools and possibly sang Irish songs there and who have failed because they never really tried earnestly to bring up their children as Irish speakers. Dun Laoghaire would put many of them to shame, and more’s the pity. What was done in the Dunbeacon school by Tadhg O Foghlu, according to one of his pupils, and what has been done in a Dun Laoghaire home where the school work was backed up by the parents enthusiasm can be done everywhere else quite as well, for neither Dun Beacon nor Dun Laoghaire are in or near the Gaeltacht.